By Alexandra Paterson

When we talk about the land of Illinois as a ‘flatland,’ we’re talking about the land’s surface—and its present. But looking into its geological history gives us a more dynamic sense of the land’s history, as well as its variety of topographies over time. In a sense, geological study is a way of unflattening the land we see, both here and elsewhere. It shows us a version of the land beneath us that is in continuous motion, changing shape all the time. Literature, too, is good at unflattening. Its ability to draw out a multiplicity of stories and narratives about the land we live on complements and expands the literal unflattening of geological history with a metaphorical unflattening.

The scientific discipline of geology that we recognize today has its roots in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Long before the discovery of plate tectonics, the history of the destruction and formation of continents and other geological phenomena were being discovered in the layers of rock strata and the fossils within them. Geological evidence—like the layers of the strata and fossils—provided some answers to mysteries about the origin and duration of the earth. But they provoked even more questions about it.

The following passages take us away from the fields of Illinois and across the Atlantic, unflattening a different locale. These two examples of geological inquiry, though separated by almost 20 years, describe the discovery of fossil shells in the same local area of Sussex, on England’s south coast. They offer us a useful contrast between the account of a natural historian, Gilbert White, and a poet, Charlotte Smith, who uses poetic form to extend beyond the particularities of the shells to explore their connection with a wider history of the land and the people who inhabit it.

In the third letter of Gilbert White’s popular A Natural History of Selborne (1789), we see a fairly typical encounter with geology for a gentleman-naturalist at the end of the eighteenth century:

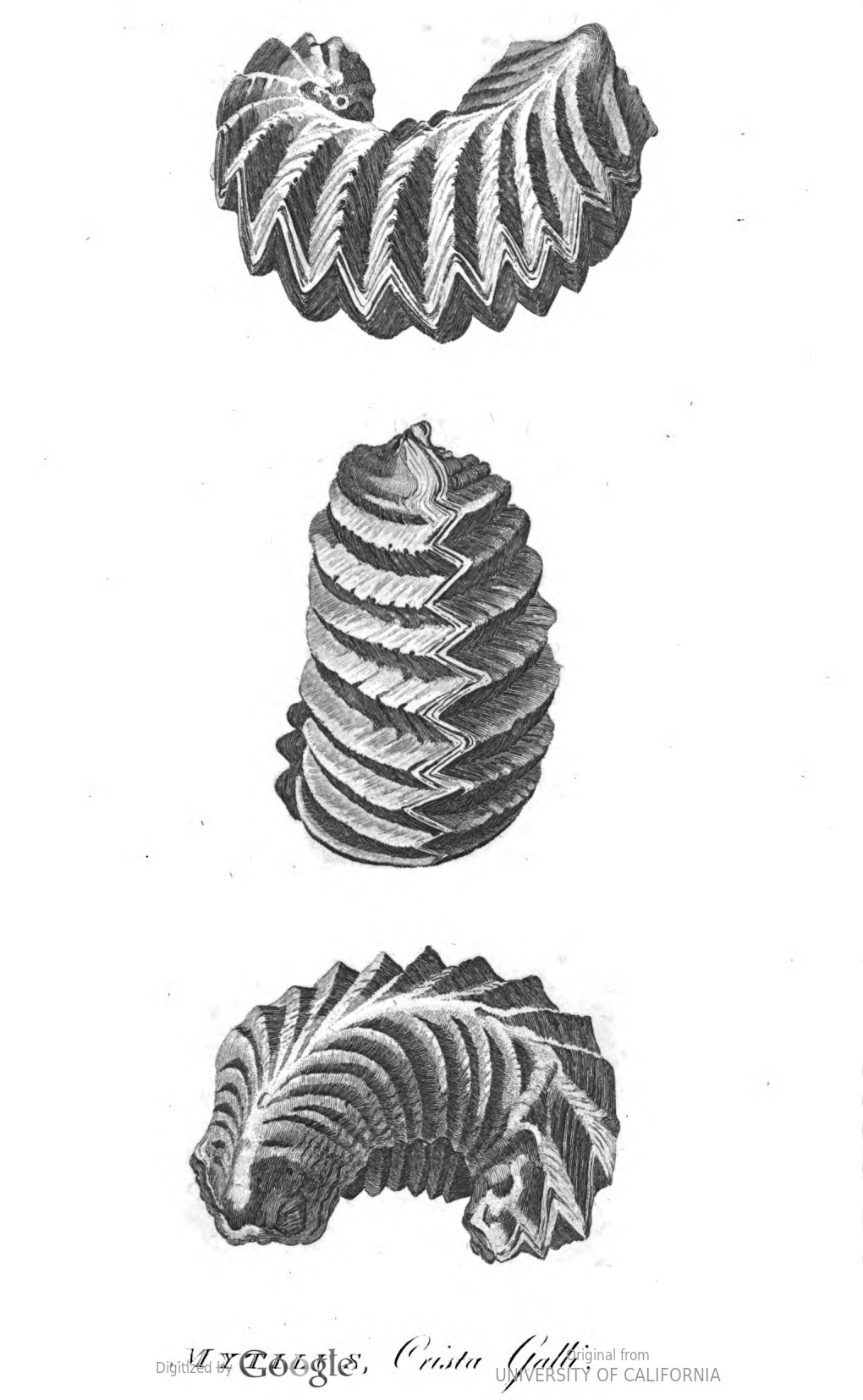

The fossil shells of this district, and sorts of stone, such as have fallen within my observation, must not be passed over in silence. And first I must mention, as a great curiosity, a specimen that was ploughed up in the chalky fields, near the side of the Down, and given to me for the singularity of its appearance, which, to an incurious eye, seems like a petrified fish of about four inches long, the cardo passing for a head and mouth. It is in reality a bivalveof the Linnaean Genus of Mytilus, and the species of Crista Galli [...] Though I applied to several such in London, I never could meet with an entire specimen; nor could I ever find in books any engraving from a perfect one. In the superb museumat Leicester-house, permission was given me to examine for this article; and though I was disappointed as to the fossil, I was highly gratified with the sight of several of the shells themselves in high preservation. This bivalve is only known to inhabit the Indian ocean, where it fixes itself to a zoophyte, known by the name Gorgonia. The curious foldings of the suture the one into the other, the alternate flutings or grooves, and the curved form of my specimen being much easier expressed by the pencil than by words, I have caused it to be drawn and engraved.

His account of the fossil shell given to him includes information about its genus and characteristics—a mytilus bivalve with curious “foldings” that are“much easier expressed by pencil than by words”—and suggests something of its origin too: an inhabitant of the Indian Ocean, it has travelled by some means to the Sussex coast. White, too, travels to discover this information. With the interesting specimen in hand, he applies to both books and private museum collections to find out more. And while he introduces the fossil under a distinctly local category, “[t]he fossil-shells of this district,” White is chiefly interested in its remove: it is foreign in origin, and exotic in description.

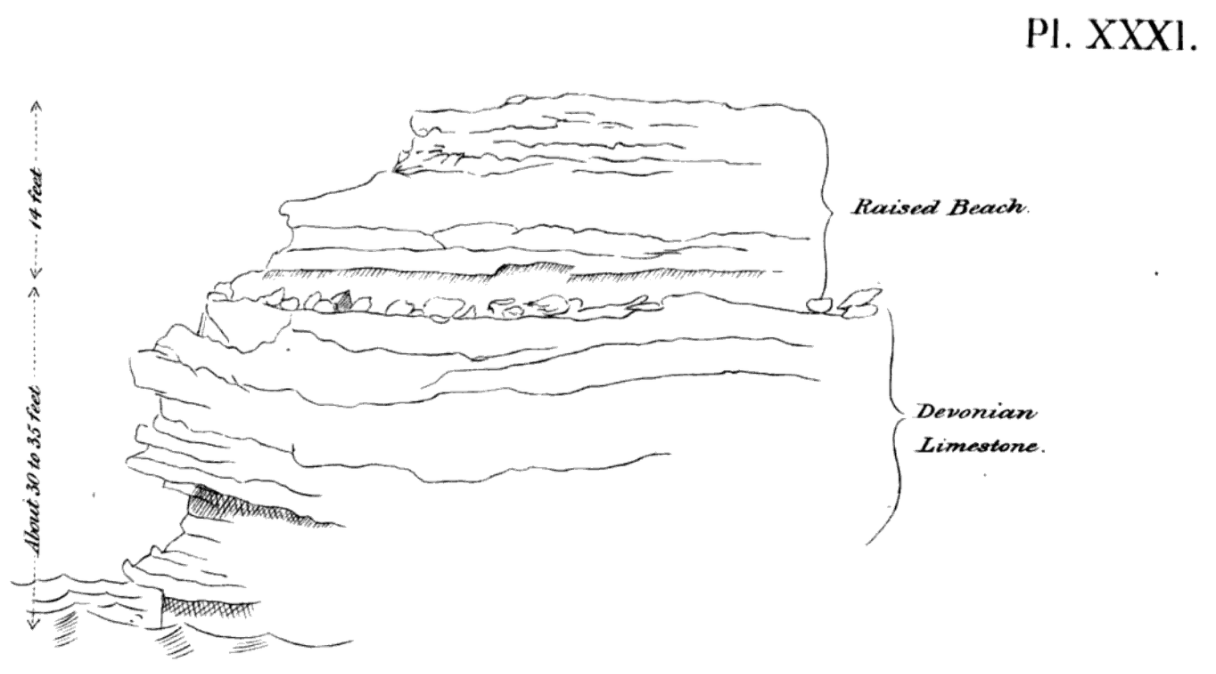

The engraving he includes with his description of it emphasizes this point. Shown at different angles against a plain background, the shell is no longer part of the chalky ground it was found in, but now an artifact.

In contrast, Charlotte Smith’s poetic encounter with similar fossil shells in Beachy Head (1807) depends on their location in her local landscape. Smith was an immensely popular poet and novelist in her day, and something of a natural historian in her own right. Unlike White’s shell, Smith’s remain embedded in the chalk rock of Beachy Head—a headland on England’s south coast, near Smith’s childhood home. Smith observes fossil shells in the chalk rock and poses questions about their history and origin, describing competing scientific explanations but never settling on just one of them:

Ah! hills so early loved! in fancy still

I breathe your pure keen air; and still behold

Those widely spreading views, mocking alike

The Poet and the Painter’s utmost art.

And still, observing objects more minute,

Wondering remark the strange and foreign forms

Of sea-shells; with the pale calcareous soil

Mingled, andseeming of resembling substance.

Tho’ surely the blue Ocean (from the heights

Where the downs westward trend, but dimly seen)

Here never roll’d its surge. Does Nature then

Mimic, in wanton mood, fantastic shapes

Of bivalves, and inwreathed volutes, that cling

To the dark sea-rock of the wat’ry world?

Or did this range of chalky mountains, once

Form a vast bason, where the Ocean waves

Swell’d fathomless? What time these fossil shells,

Buoy’d on their native element, were thrown

Among the imbedding calx: when the huge hill

Its giant bulk heaved, and in strange ferment

Grew up a guardian barrier, ’twixt the sea

And the green level of the sylvan weald.

In this passage, she observes fossil shells in the chalk rock and poses questions about their history and origin, describing three competing scientific explanations but never settling on just one of them. In doing so, she allows these competing narratives to coexist, and goes on to explore how others relate to the same land—the herdsman who has no idea about the land’s geological history, the historian who looks for evidence of past conquests in it, and the peasants who, finding elephant bones in the ground, believe giants once lived on the land.

As she takes us across the landscape with her descriptions, the multiplicity of narratives and experiences that emerge offer us something that a two-dimensional—and flat—map can’t. It also offers an alternative to White’s more straightforward approach to historical narrative. Instead of a linear depiction of a single historical narrative, she offers several narratives that are not flat but complexly intertwined and layered, and in doing so she reminds us how rich and complex all our histories are, whether geological, social, or personal. Long before we had any notion of an Anthropocene, Smith was aware that our history and geological history were not separate things.

While White searches for specific information about his fossil shell, Smith allows her shells’ competing narratives to coexist. Perhaps fossilized facsimiles of shells exist on dry land, playfully placed there by “Nature,” or maybe the fossils’ presence indicates that this dry land was once part of the ocean. Both histories inform her response to the land, as they are shown to be embedded not only in Beachy Head’s chalk rock, but also in a complex layering of histories of the land that include Smith’s personal history, social and ancient histories, and the land’s wider geological history. As the poem continues, Smith explores how others relate to the same land—the herdsman who has no idea about the land’s geological history, the historian who looks for evidence of past conquests in it, and the peasants who, finding elephant bones in the ground, believe giants once lived on the land:

from whence

These fossil forms are seen, is but conjecture,

Food for vague theories, or vain dispute,

While to his daily task the peasant goes,

Unheeding such inquiry; with no care

But that the kindly change of sun and shower,

Fit for his toil the earth he cultivates.

As little recks the herdsman of the hill,

Who on some turfy knoll, idly reclined,

Watches his wether flock; that deep beneath

Rest the remains of men, of whom is left

No traces in the records of mankind,

Save what these half obliterated mounds

And half-fill’d trenches doubtfully impart

To some lone antiquary; who on times remote,

Since which two thousand years have roll’d away,

Loves to contemplate. He perhaps may trace,

Or fancy he can trace, the oblong square

Where the mail’d legions, under Claudius, rear’d

The rampire, or excavated fossé delved;

What time the huge unwieldy Elephant

Auxiliary reluctant, hither led,

From Afric’s forest glooms and tawny sands,

First felt the Northern blast, and his vast frame

Sunk useless; whence in after ages found,

The wondering hinds, on those enormous bones

Gaz’d; and in giants dwelling on the hills

Believed and marvell’d—

As she guides us across the landscape, the multiplicity of narratives and experiences that emerge offer us something that a two-dimensional—and flat—map can’t. The poem offers an alternative to White’s more straightforward approach to historical narrative. Instead of a linear depiction of a single historical narrative, Smith offers several narratives that are not flat but complexly intertwined and layered, and in doing so she reminds us how rich and complex all our histories are, whether geological, social, or personal. Today, the concept of the Anthropocene, a geological epoch marked by human intervention—such as the introduction of plastics—is beginning to collapse geological and human history. Humans are making their mark not only on catastrophic climate change but on the geological structure of our planet. But even at the turn of the nineteenth century, long before we had any notion of an Anthropocene, Smith was aware that our history and geological history were not separate things.

check out other Flatland contributions below