By Samantha Good

At the beginning of the fellowship year when our group decided on the concept of “flattening” as the focus of our group study and the concept which would guide our conversations for the year, I was skeptical of the utility of it for my own research. While the concept is quite apt for the study of the expansive farmlands of Illinois, I was, at first, baffled as to how flattening could relate to my work as a scholar of Latin American literature, more specifically Andean texts.Known for its alpine topography, the Andes evoke the exact opposite of flatness.Moreover, the ability of Andean civilizations to harness the ecological diversity of this region and to develop adaptive strategies to overcome the difficulties the topography posed is truly remarkable and something at which scholars across many disciplines marvel.

So I sat with the concept of flattening for a while, thinking beyond the geographic notion of flatness in order to consider other forms of flattening. My current research focuses on the long 19th century in the Andean nations of Bolivia and Chile, examining how attitudes and practices towards the environment were in flux during this time period. In the latter half of the 19th century and first decades of the 20th century, with the adoption of paradigms of liberalism, Latin American nations were further and more intensely integrated into global market relations, most frequently as exporters of “raw” or primary commodities (with significant environmental implications). Due to this increased involvement in global capitalist markets, some scholars with Latin American ecocriticism have characterized this century as a time period of extensive environmental degradation. Though this era was certainly one of significant change with regards to practices and attitudes towards the environment, a more nuanced understanding of this foundational time period in these nations is merited.

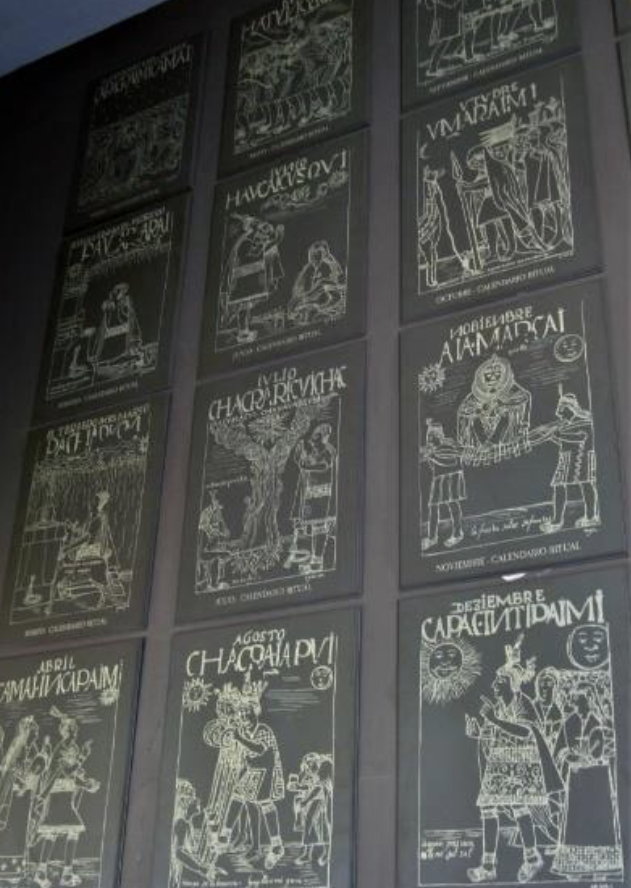

This notion that the 19th century was an era of degradation and unrestrained exploitation can partially be attributed to the weight given to canonical texts of the time period and to limitations of the archive. In 19th century literary and cultural forms, criollonation builders attempted to put forth an image of totalizing or sweeping change with regards to modernizing processes as well as whitening/miscegenation (mestizaje). In their efforts to craft this image of modernity, many criollo authors erased the diversity of practices and attitudes towards the environment which existed in these Andean nations, often relegating indigenous modes of dwelling with the land to the colonial or pre-Columbian past. Thus, in a sense, these authors flattened the various complex world-making activities which defined life in the Andes during this time period.

However, in Bolivia where the indigenous population was the majority and dispersed throughout the entirety of the territory, Bolivian elites had to work hard to negate the influence of indigenous peoples on national culture. For example, in her book Trials of Nation Making, Brooke Larson notes that around 1840, it was estimated that 80 percent of the Bolivian population was indigenous and that fewer than 20 percent of Bolivians spoke Spanish (204).

Recently within the environmental humanities, the concept of thickening has been discussed as a way of addressing gaps in knowledge by “adding layers of meaning and significance to our experience and understanding of reality” (Hulme 334). My current research works against these forces of flattening and to recover the plurality of voices and perspectives of marginalized peoples in the Andean region. What my project works to do is to complicate this vision, by examining instances of negotiation between indigenous and creole world views and then considering how this has impacted attitudes towards the environment. An analysis of a variety of literary and cultural forms from the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century demonstrates that, in reality, a complex negotiation of world views and attitudes towards the environment was happening during this first century of nationhood in both Chile and Bolivia. By delving into sources which have not traditionally been deemed “canonical” 19th century texts, it is possible to perceive how certain groups of people in the Andes dwelled deeply with the landscape, even in the face of sweeping modernization.

Bibliography

Hulme, Mike. “‘Gaps’ in Climate Change Knowledge.” Environmental Humanities, vol. 10, no. 1, 2018,330–337.

Larson, Brooke. Trials of Nation Making: Liberalism, Race, and Ethnicity in the Andes, 1810 1910.Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004.

check out other contributions to Flatland below